ACCESS, RIGHTS AND PRIVACYGENDER REPRESENTATIONINAUGURAL SESSIONACCESSDIGITAL LITERACY AND EMPOWERMENTPRIVACYFREEDOM OF EXPRESSIONDELHI TECH TALK BY CCG, DEF, IDP, SFLC, HASGEEK, CIS, IT FOR CHANGECONCLUSION AND WAY FORWARDPARTICIPANTS AT DIGITAL CITIZEN SUMMIT 2017

India and other South Asian countries have leapfrogged on the technology spectrum, from specialised institutional use to everyday use in our increasingly digital lifestyles. In this context, it has become vital to generate multi-stakeholder dialogue on the context and definition of ‘digital citizen’ in order to shape our digital future. It was keeping this imperative in mind that Digital Empowerment Foundation (DEF) in association with Friedrich Naumann Stiftung für die Freiheit and UNESCO organised the second edition of Digital Citizen Summit on September 21 and 22, 2017, in New Delhi. The summit was also supported by Association for Progressive Communications (APC) and The Internet Society.

Four parameters of citizen’s digital rights formed the Summit’s core focus, namely: Access, Privacy, Freedom of Expression, and Digital Literacy and Empowerment, with the objective to find a solution to bridge the digital divide and to create a platform for youth, women and social media enthusiasts to raise awareness about internet rights, digital literacy, and digital security.

The summit aimed to develop a multi-stakeholder dialogue platform along the model of Internet Governance Forum, with the objective of generating actionable policy recommendations. It emphasised a citizen-centred perspective in deliberations on the intersections of online and offline spaces created by us and further aimed at promoting human rights online. In order to achieve this, the summit aspired to provide a platform for building strategic partnerships between citizens and other relevant stakeholders comprising scholars, technologists, academics, civil society organisations, and government representatives.

This year, more than 200 representatives from seven countries from Asia Pacific. Argentina, and South Africa participated in the summit.

SUMMIT FORMAT AND THEMES

DCS 20117 was designed to have a series of 20 sessions divided into three parallel sessions organised along the four key summit themes over two days. The sessions were structured into four types, namely: Open forum, Panel, Roundtable, and Workshop. The series of parallel sessions related to the following sub-themes of the summit:

- Access – Infrastructure, network-neutrality, access to information, free data and equal rating, broadband connectivity, zero rating, affordability, accessibility, usability, last mile connectivity, network discrimination, uniform access, etc.

- Freedom of Expression – Hate speech, open access, online violence against women, censorship, online protest, freedom to religion, human rights, network shutdown, etc.

- Privacy – Digital security, cyber security, big data, surveillance, data protection, right to be forgotten, encryption, anonymity, right to privacy, etc.

- Digital Literacy and Empowerment – Advancing literacy through ICT’s, internet economy, youth engagement, enhancing accessibility for persons with disability.

A key aspect of DCS 2017 was to have fair gender representation. This was communicated to all organisations when sessions proposals were being evaluated. Issues regarding gender and sexual rights featured heavily during the summit and this was reflected in the number of speakers’ and attendees. The summit had sessions covering aspects of alternative access models for gender and sexual expression online, and women’s and minority rights online were given space for discussion.

Three aspects of representation and equity were considered when conducting this gender-mapping activity. First, it was ensured that each panel was representative of diversity. Gender and minority representation, stakeholder representation, and issue priority were key criteria of diversity. Second, equal participation was ensured for audience, speakers, and panelists in terms of numbers and speaking time. Third, deliberation on gender issues was encouraged for all sessions. Certain sessions focused directly on gender and sexuality, while others included a gender lens in broader debates. Thus women’s access to and use of technology emerged strongly even in a more general discussion on access and last mile connectivity in a session like Connecting India’s Billion by The Dialogue. The session highlighted how use of technology is especially a game changer for women and other marginalised groups in society. Several sessions focused on the mixed relationship of women, LGBTQI, disabled, and the elderly with technology. Don’t Let it Stand, How to hold a Wikipedia edit-a-thon, and Are you part of your city’s map? are some examples of sessions that brought attention to the complicated nature of women’s interaction with technology. ICTs have emerged as enabler of exercise of rights as well as another space where abuse and harassment is reproduced. These sessions contributed to evolving strategies for amplifying the positive impact of ICTs for women and marginalised, while mitigating their negative implications.

Gender participation was broadly equal during DCS this year. Out of 65 speakers, 31 were women. The sessions that especially focused on issues of gender and sexuality saw stronger participation of women and LGBTQI persons. Over the days, DCS 2017 had around 250 attendees, out of which a little less than half were women. Overall, the panels were balanced in terms of gender representation. DCS hopes to preserve and further encourage inclusivity in next year’s summit among women, LGBTQI persons and ethnic minorities, enabling participation of audience, speakers, and panelists and widening the scope of issues raised, speakers and panelists, and participants.

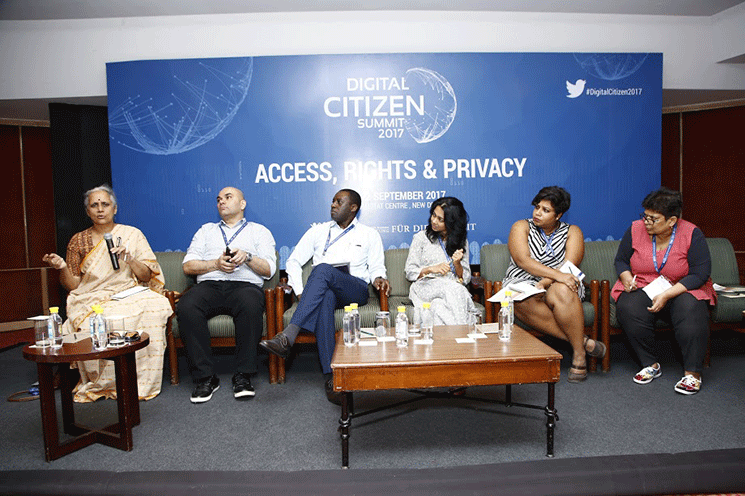

The Inaugural Session of Digital Citizen Summit 2017 kickstarted the event with an interactive discussion on key issues of access, rights, and privacy. The interaction was led by core panelists representing different areas of expertise. The panel comprised Usha Ramanathan, legal researcher; Rajnesh Singh, Internet Society Asia-Pacific Regional Director; Al-Amin Yusuph, UNESCO South Asia Communication and Information Advisor; Chinmayi Arun, Executive Director, Centre for Communication Governance, National Law University (Delhi); and Gayatri Khandhadai, representing Association for Progressive Communications. It was moderated by Bishakha Datta from Point of View. Each panelist deliberated upon the key issues in their area and responded to questions and concerns from participants.

PARTICIPANT CONCERNS

- Citizenship even in the real-world has been unable to deliver rights and belonging, excluding categories of individuals termed refugees, residents, migrants, etc. from accessing rights and entitlements.

- How can ordinary people start viewing privacy as a right in everyday life, and whether privacy given away voluntarily is of a different nature to intrusions into privacy?

- Those occupying power in governments often dictate terms of welfare and set limits to rights, shrinking citizens’ right to freedom of expression.

- Who has the power to design Internet architecture? The onus of security should not be on users but must be made part of technology by design as ordinary people can do very little to secure themselves.

- We have been unable to create networks of trust to relate with each other freely and in a safe way over the Internet.

- What are the ways in which accountability can be ensured in the Internet ecosystem?

PANEL HIGHLIGHTS

“Why shouldn’t we shift the focus from why data should not be collected from us to by how much and what kind of data should be collected Global companies use data to make money, so why are we not benefiting from the data we are giving them? We have to mitigate abuse and work together in a participatory manner”

Al-Amin Yusuph

“Governments across the world have huge drives to go digital, but there are several other challenges to this task for example unreliability of electricity. In India, it is becoming almost fashionable to shut down the Internet, while also promoting Digital India and cashless economy. We must ensure that everyone has equal opportunities in the digital.”

Rajnesh Singh

“Saying that users are responsible for their own privacy is like saying women are responsible for their own safety when public spaces are not made safe. Architecture is important, and we need to architect for the right to privacy.”

Chinmayi Arun

“Internet has fundamentally changed many rights, which are getting impacted because of technology. There are some rights we have been able to access only because of technological development.”

Gayatri Khandhadai

“People say data is the new oil. Oil has already produced so many wars, do we really need new wars?”

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- In the context of the recent Privacy Judgment, we must carefully consider and account for what the idea of digital is producing for those in power, and ensure that our digital ambitions are for citizenship rather than for appropriation.

- When we promote the Internet, we must also be aware of the implications and challenges of the digital, and to make sure it is through equitable socioeconomic development so as to prevent new digital divides from emerging.

- The future of Internet is potentially under threat as we see the level of trust diminishing, with questions of privacy, data breaches, and citizens often not trusting their own governments because of surveillance.

- While discussing digital spaces, we must keep in mind that access to technology can be and is taken away without accountability or appeal, as in the case of network shutdowns.

- The idea citizenship is to make the State accountable. Therefore it is an important exercise of citizenship to regularly make the State accountable and to work responsibly for everyone’s rights.

- The right to privacy exists beyond the Constitution and is a basic human right. Therefore, the governance systems we design should emphasise proportionality, and involve only minimal violation of rights.

The summit’s first theme focused on access, under which the following sessions were organised:

- Connecting India’s Billion by The Dialogue (Panel).

- Optimal Access to Financial Infrastructure for Sustainable Growth of Digital Financial Services: Examining the Role of Regulation and Competition by CUTS International (Roundtable)

- LibreRouter: A Router for Community Networks by Community Networks by AlterMundi (Workshop)

- Open eGovernance Index by Foundation for Media Alternatives (Roundtable)

- Accessibility and technology for all by Society for Rehabilitation of the Visually Challenged (Open Forum)

- Are you part of your city’s map? By Hidden Pockets (Open Forum)

Connecting India’s Billion by The Dialogue deliberated on access and last mile connectivity, with a focus on innovative actionable solutions and technological alternatives such as white spectrum and public Wi-Fi for getting people online. The solutions discussed aimed at ensuring that growth propelled by mobile Internet access reaches the lives of poorest of the poor. Discussion also touched upon the ‘BharatNet’ project. The panelists included Nalini Srinivasan, PhD Scholar at IIT Delhi; Dr. Vigneshwara Ilavarasan, Department of Management Studies, IIT Delhi; Raman Jit Singh Chima from Access Now; and Osama Manzar from DEF. It was moderated by Ranjeet Rane from The Dialogue.

<strong”>Optimal Access to Financial Infrastructure by CUTS International framed the discussion on present state of regulation and competition in the digital infrastructure market and its impact on access to digital financial services from the perspective of competition and consumer welfare. Discussion focused primarily on the Indian regulatory regime for digital financial services and how specific regulations may promote or obstruct competition, thereby affecting consumer welfare and access to digital financial services. The session speaker was Amol Kulkarni representing CUTS International, who deliberated upon the various regulatory issues affecting access to digital financial infrastructure, and proposed measures required for facilitating optimal access.

LibreRouter by AlterMundi involved a technical demo of AlterMundi’s LibreRouter, an Open Software Open Hardware Router for and by Community Networks. It was conducted by Nicolas Andres Pace, core developer of the LibreRouter project. As a community network, LibreRouter has been developed in the context of and aims to connect villages and people in Latin America. It offers great potential for adapting to different conditions as various types of equipment are used to set up these networks. A LibreRouter is used as a central point which is customised with software to connect with different devices. They also use power batteries, or stable electrical supply before setting up the network. Router and devices connected in high frequency Wi-Fi tower to receive signals. The Wi-Fi Router comes with a password through which the community can use Internet on their devices.

Open eGovernance Index by Foundation for Media Alternatives (FMA) from the Philippines and was presented by FMA Executive Director Liza Garcia. The Open E Governance Index (OeGI) is a normative tool developed for assessing and comparing how different countries are utilising openness in network societies to enhance public service, citizen participation and engagement, and address communication rights. It is part of an action-research project that aims to develop a quantitative tool to gauge the state of e-Governance around the world, and has studied the same in Hong Kong, Pakistan, Philippines and Thailand in Asia, and Uganda in Africa, and Colombia in South America. The study encourages multistakeholder engagement with policy, and aims to assess vulnerabilities in order to recommend alternatives, amendments, and modifications to pre-existing national e-governance policies. Liza expressed the hope to expand the study to more countries, including India, in the future.

Accessibility and Technology for All by Society for Rehabilitation of the Visually Challenged highlighted the issues surrounding access to technology for people with disabilities and the elderly. It was presented by Sunil J Mathew from the Society for Rehabilitation of the Visually Challenged, which works on providing opportunities of employment to the visually challenged by taking advantage of technology especially in telemarketing and computer training.

Are you part of your city’s map? by Hidden Pockets generated discussion on access to inclusive sexual and reproductive health services in cities. It included a tech demo of Hidden Pockets’ feminist cartography project in which they are mapping reproductive and sexual health service providers in the global south. It was facilitated by Jasmine George from Hidden Pockets. This session was an apt demonstration of how successful civil society initiatives such the one by Hidden Pockets can make technology more inclusive and meaningful by letting people map their own cities through locating important and sensitive services, reviewing them, making them publicly accessible in order to de-stigmatize them, and curating places of interest, pleasure, and services by making their own narratives of city life part of its map. Such initiatives not only help in designing more inclusive, user-generated maps, but also have the potential to make cities inclusive spaces.

ACCESS: OUTCOMES AND RECOMMENDATIONS

| SESSION | RECOMMENDATION | TARGET STAKEHOLDER |

|

Connecting India’s Billion by The Dialogue |

Market forces will not be able to determine investment in infrastructure in India’s remote and sparsely populated areas, as a small and dispersed population does not justify a business to implement a network. |

Government needs to determine a basic basket of services reaching the remotest destinations using multiple devices, including telemedicine and mobile banking. Such access measures can be merged with pre-existing services, such as ASHAs. |

| Promotion of handheld smart devices is a better alternative for ensuring access than traditional computers, as they work better in the context of unreliable electricity and restrictions on women’s mobility. |

Government |

|

|

The pilot survey study of 10,000 people in areas where BharatNet has been implemented conducted by Dr. Vigneshwara Ilavarasan shows that 70% had no information on it, there is low level of personal and business related Internet use, and there is presently low demand and motivation to adopt it. |

Government should improve information dissemination and evolve a more effective business model for experimenting with infrastructure through collaboration with private bodies and CSOs for household-level delivery. |

|

|

Internet should meaningfully protect people’s rights, and human rights should be incorporated as a top level issue as it is linked to demand drivers. Human Rights Principles for Connectivity and Development evolved by Access Now is an example of a guiding framework. |

Private sector investment in connectivity should be deployed hand-in-hand with human rights based capacity building, public access points, and skill development. Investors should support connectivity for development that supports human rights. | |

| Recognise the need to build high capacity networks to be able to support video in order to connect the next billion who may not be able to access the Internet through text, especially in English. |

Governments, Multilateral Organisations |

|

| Encourage localisation and development of local language content. If we create a system where it is hard for anyone to immediately deploy a website or deploy a service on the Internet, we actually reduce the value of the Internet and instead increase its demand drivers. | Internet Ecosystem | |

| Optimal Access to Financial Infrastructure for Sustainable Growth of Digital Financial Services: Examining the Role of Regulation and Competition by CUTS International |

Frame the debate on digital financial service sector regulation in terms of consumer welfare indicators like access, affordability, systemic risk management, grievance redressal, and cost and quality of digital financial services. Since a major challenge in India is consumer uptake of digital financial services, even when available. |

Policy Forums |

| LibreRouter: A Router for Community Networks by Community Networks by AlterMundi | Innovate and invest in alternative solutions for access which enable communities, irrespective of technical background, to deploy networks by themselves and extend the reach of ICTs. Such solutions, of which LibreRouter is a successful model, should be aimed at empowering communities to provide themselves with ICTs. |

Civil Society Organisations |

| Open eGovernance Index by Foundation for Media Alternatives | Develop alternative indices for comparison of governmental use of ICTs to provide public service and for the benefit of citizens. Such research enables comparison of national policies and practices of different countries in terms of their strengths and weaknesses, and enable civil society organisations to engage with governments through concrete, evidence-based policy recommendations. | Civil Society Organisations, Academia |

| Accessibility and technology for all by Society for Rehabilitation of the Visually Challenged | Identify the multiple levels on which technological gaps exist people with disabilities and the elderly in concrete cases. Generally, these exist on (i) devices: most have access only to low end devices (nonsmartphones) which don’t work the way the visually challenged community wants, braille devices are expensive; (ii) apps and websites: 75% of government websites are not accessible to blind people in India. | Technical community can adopt certain design principles to improve the accessibility of essential websites and online services, and bridge the gap for people with disabilities in accessing technology. In app design, for example, the following criteria can be ensured to improve accessibility: using large and bold text, reduce motion and clutter on the apps, increase and decrease in contrast, reducing transparency by adding background, and include customised sensors which can detect motion, acceleration, gravitational and gyroscope. |

| Efforts should be made to develop an ecosystem for the technical community consisting of developers and architects to contribute to code and help develop accessible technology solutions for persons with disability and elderly users. | Governmental and private sector support is required to develop and implement these innovations and solutions. |

The summit’s second theme focused on Digital Literacy and Empowerment, under which the following sessions were organised:

- Mobile campaign for social change by Amnesty International India (Open Forum)

- Silencing Voices: Worrisome state of restricting religious and political dissent in the sub-continent by Center for Social Activism and Bytes for All (Panel)

- How to hold a Wikipedia edit-a-thon and reduce its gender gap by Feminism in India (Workshop)

- Digital literacy as a tool for self-empowerment by F-infotech (Open Forum)

- Social media’s complicated relationship with sexual content and expression of LGBTQI and disabled persons by Hidden Pockets and Point of View (Panel)

- Active Citizenship and Digital Charter by MediaNama and DEF (Workshop)

- Regulating Search Engines: Competition, Free Speech and Human Rights by Centre for Communication Governance, National Law University Delhi

The first session, <strong”>Mobile Campaigning for Social Change, organised by Amnesty International India, demonstrated the example of a successful campaign encouraging participation through mobile phones. The session speaker was Padmaja Karra, representing Amnesty International India. Amnesty International has used mobile phone campaigns using missed call facilities to mobilise people for human rights, and were able to collect 2.5 million signatures in two years. While any campaign for social change, whether online or offline, needs to have an integrated approach incorporating several components such as research, advocacy, etc., in order to effectively mobilise public. The key learning from their campaign was that mobile technology works best for mobilisation out of all the ICTs devices.

Silencing Voices: Worrisome state of restricting religious and political dissent in the sub-continent by Center for Social Activism and Bytes for All focused on the intersection of religion and freedom of speech online, and also touched upon hate speech. The panelists included Aklima Ferdows Lisa, from Center for Social Activism, and Pranto Polash, a Bangladeshi journalist now residing in India who has been a victim of Section 57 of the Bangladesh ICT Act. It was moderated by Gayatri Khandhadai, representing Association for Progressive Communications (APC). While the session’s main focus was the situation of restricting freedom of expression under the vague Section 57 of the ICT Act in Bangladesh, it was contextualised in the worrisome global trend of criminalising blasphemy, State repression, and justifying restrictions on freedom of expression.

The session highlighted the Bangladeshi case, which serves as a useful study in the issue due to the history of its reputation as a liberal, secular, and moderate country, which drastically changed in the face of blogger killings and restrictions on freedom of expression in recent years. The Bangladesh ICT Act was enacted in 2006, with the stated objective to ensure freedom of information among the people and to enable their right to information in its preamble. It was amended first in 2009, and then majorly once again in 2013. Right to information essentially means accountability and transparency in all spheres, whether public or private, and thus it was not problematic at first. When amended in 2013, however, the objective was changed with amendment to growth of ecommerce and information technology. Following this amendment, which increased the term of imprisonment from 10 to 12 years and removed the requirement for police/law enforcement agencies needing warrant from local authorities, the Act was routinely used to target online activists and journalists.

The case of misuse of law to silence freedom of speech and expression in Bangladesh provides a worrisome example of state repression of rights. However, religion-based restrictions on freedom of expression and growing religious intolerance is a trend for many religions across the world, including in India, and is not limited to any one religion or region.

<strong”>How to hold a Wikipedia edit-a-thon and reduce its gender gap by Feminism in India

was a workshop teaching participants how to organise, research, and hold their own Wikipedia edit-a-thons. The session was facilitated by Asmita Ghosh, representing Feminism in India. The objective of this workshop was to reduce the gender gap on Wikipedia by teaching and promoting women and other marginalised persons to edit on Wikipedia in order to ensure their representation on the world’s most popular and democratic resource portal. Feminism in India holds these edit-a-thons once every month, and has managed to create over 80 Wikipedia pages through such workshops. Thus, it is a successful model of how digital gaps and gender disparities can be reduced by community and civil society initiatives.

<strong”>Digital literacy as a tool for self-empowerment by F-infotech demonstrated the ways in which digital literacy can address India’s socio-economic problems by aiding people in developing self-learnable and self-sustainable skills, leading to self-empowerment. The session speaker was Gauthamraj Elango, who shared his experiences regarding the positive impact of digital literacy from running a cyber cafe in Perundurai, a small town in Tamil Nadu.

<strong”>Social media’s complicated relationship with sexual content and expression of LGBTQI and disabled persons by Hidden Pockets and Point of View focused on issues pertaining to sexual expression of the LGBTQI community, women, and persons with disability as well as social media as a means to salvage gendered spaces. The panelists included Nadika, a trans rights activist; Smita Vanniyar, Point of View; Mahika, Feminism in India; Jasmine, Hidden Pockets; and Nipun Malhotra, Nipman Foundation. It was moderated by Brindaalakshmi. K, from Hidden Pockets. The session highlighted the mixed nature of relationship queer and disabled persons have with social media. On the positive note, Internet enables individuals to exercise certain rights and privileges – right to choose by determining what and how much one wants to disclose about themselves, right to information by engaging in different groups, right to anonymity by creating new identities, right to expression by voicing out opinions, and right to association or assembly by developing communities. However, while Internet has become a path to empowerment for those who can access it, inaccessibility has remained a major challenge for a good majority.

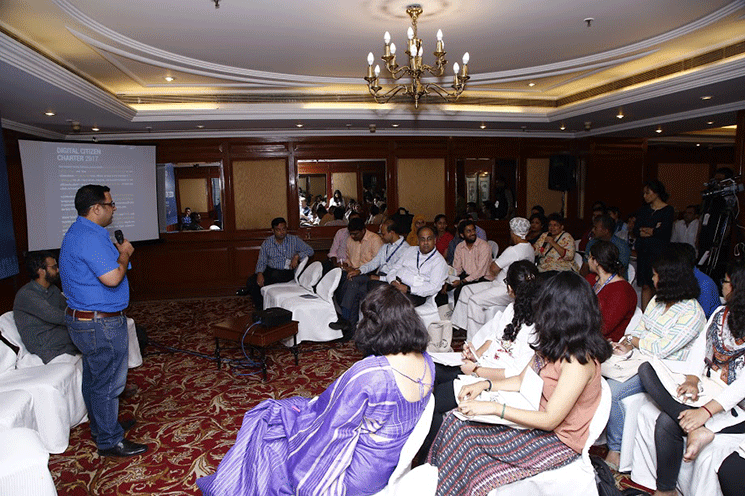

In the session Active Citizenship and Digital Charter by MediaNama and DEF, DEF released the Digital Citizen Charter 2017, a compilation of the qualities of the internet that netizens would like to see shape the internet of the future. The charter was crowdsourced with contributions from students around Delhi and online submissions. The audience was asked to emphasise on free and equal access, an Internet that stays ‘on’, free from prejudice and interference, and one where freedom of expression thrives in their contributions.

Nikhil Pahwa of MediaNama took this discussion forward and engaged the audience on Active Citizenship and reclaiming civic life. He sought suggestions from audience members on how citizens can hold governments and private bodies accountable. Shravya, a LAMP fellow, suggested that as citizens we need to “ask why”- ask why we need to do the things asked of us, and ask why entitlements have not been delivered. Meghnad, a policy specialist turned creator of YouTube videos, talked about educating people about their rights and the constitution via social media. Gayatri Khandadhai of APC suggested that “trolling a troll” could be an efficient way of checking behaviour online. Eshita Mukherjee of DEF suggested that an online repository of procedures for making complaints or raising issues which would be accessible to the layman was required.

<strong”>Regulating Search Engines: Competition, Free Speech and Human Rights organised by Centre for Communication Governance, National Law University Delhi

, focused on different forms of regulation of search engines, which do not create their own original content, but instead serve as intermediaries. It was contextualised in the global trend of increasing requests made by government bodies to search engines for regulating their platforms. The discussion was framed in the right to free speech and expression in the face of such regulatory methods, and also touched upon the right to be forgotten. It included the following panelists: Rupsa Mallik from CREA; Smriti Parsheera from National Institute of Public Finance and Policy; Sushant Sinha, founder of Indian Kanoon; and Amrita Vasudevan representing IT for Change. It was moderated by Prasanth Sugathan from SFLC. The panelists of this session represented different stakeholder groups, and thus addressed a unique concern each from different fields of expertise, namely: corporations, human rights organisations, academia, and legal expertise.

DIGITAL LITERACY AND EMPOWERMENT: OUTCOMES AND RECOMMENDATIONS

| SESSION | RECOMMENDATION | TARGET STAKEHOLDER |

| Mobile Campaign for Social Change, organised

by Amnesty International India (Open Forum) |

Mobile phones are effective for mobilising large-scale campaigns for social change as they offer the advantages of having a great physical reach, have the ability to deliver information with voice reducing the need for literacy, and offer the possibility of increased grassroot level communication through messages delivered in regional languages. |

Civil Society Organisations |

| How to hold a Wikipedia edit-a-thon and reduce its gender gap by Feminism in India (Workshop) | Regularly organising Wikipedia edit- a-thons not only promotes diversity and representation online in terms of closing the gender divide and in content, but also aids digital literacy and empowerment among women and marginalised groups by teaching them skills of research, text editing, and content creation. |

Civil Society Organisations |

|

Organising and promoting such capacity building workshops has the potential to also address other aspects of digital divide and access, particularly linguistic gaps, as they may be used to encourage content creation in Indian languages on pre-existing platforms such as Wikipedia. |

Civil Society Organisations |

|

|

Digital literacy as a tool for self- empowerment by F-infotech (Open Forum) |

Digital tools must be promoted not only as means of communication and entertainment, but as a foundation and source for seeking knowledge and accessing information in order to make users self-empowered. Promoting digital tools as platforms for exploring interests, developing skills, and finding opportunities is key to empowerment. |

Civil Society Organisations, Governments, Private Sector |

|

Social media’s complicated relationship with sexual content and expression of LGBTQI and disabled persons by Hidden Pockets and Point of View (Panel) |

Social media can be successfully leveraged by the queer community to build support systems and connections within itself. It can also be an effective platform to access and disseminate information about issues absent from mainstream media. |

Civil Society Organisations |

|

|

Social media can enable people marginalised communities to share grievances, experiences of discrimination, and demand accountability from service providers through online platforms. |

Civil Society Organisations |

|

Regulating Search Engines: Competition, Free Speech and Human Rights by Centre for Communication Governance, National Law University Delhi |

There is immense need for regulation of search engines in relation to competition laws. This is especially concerning as Google was found to be manipulating search results in order to favour its own interests, i.e., using its advantage in the search engine market to advance its interests in other markets. This kind of power enjoyed by a monopoly is highly consequential as it can make or break entire industries depending on where they appear on rankings. Regulation is clearly required, as corporations enjoying monopoly can use their position for unfairly manipulating the market. However, markets move faster than legislation especially in the fast moving terrain of technology today. Thus, immediate solutions may be more appropriate from the markets themselves. |

Government, Private Sector, Policy Forums |

|

|

One of the major issues regarding search engine regulation in India has been blocking advertisements for sex selection. This is a disproportionate move which will also take away important public domain information regarding sex selection. Declining sex ratio and sex selection have been profound historical problems in India, and regulation of technology will not change these attitudes by itself. There cannot only be a technological fix to a social problem. |

Government |

|

|

As users and consumers, we must stop being merely passive users of technology and recognize that we provide search engines with material. Therefore, as consumers, we must demand transparency and accountability from such platforms. |

Consumers, End Users |

The summit’s third theme focused on Privacy, under which the following sessions were organised:

- Going beyond privacy: The social justice implications of surveillance culture by Internet Democracy Project (Panel)

- Industry 4.0 and cyber security: Confronting challenges by The Dialogue (Roundtable)

Going beyond privacy: The social justice implications of surveillance culture by Internet Democracy Project

focused on privacy in relation to surveillance, which is now embedded in every aspect of life. It was moderated by Nayantara from Internet Democracy Project. The panelists included Srinivas Kodali, an interdisciplinary researcher and open data activist working on citizen data; Anoo Bhuyan, health policy journalist working at The Wire; Renu Arya, representing Feminist Approach to Technology; and Dhrubo Jyoti, a Delhi-based journalist. The panel represented a diverse set of opinions, with the inclusion of panelists supportive of surveillance measures and those critical of it. The session addressed surveillance issues from different standpoints, from its impact on gender-based inequities in access to technology, to its failure to deliver the intended public benefit due to implementation failures.

The panel brought attention to several kinds of institutions and platforms which surveil people in differential ways, such as governments, private bodies, and families.

It especially highlighted the gendered aspect of surveillance. For women in particular, surveillance by families is a pressing issue in India as it also impacts their access to technology. Gender differences in access to technology are stark in the Indian case, with women not being granted permission by their families to access and use technology. Furthermore, surveillance in the Indian cultural context is often linked to and based on issues of morality, which impacts women and women’s safety in specific, gendered ways. This gender-based monitoring prevents women from exercising their rights to access information and expression as citizens.

Industry 4.0 and cyber security: Confronting challenges by The Dialogue focused on the core tenets of cybersecurity in India, in the context of today’s connected world where most transactions whether financial or in terms of data take place online. In this context, it has become more important than to develop safe and secure Internet infrastructure and a robust cybersecurity regime. The panel included Anupam Sanghi, Delhi-based lawyer; Jayadev Parida, PhD scholar pursuing cybersecurity at Jawaharlal Nehru University and Research Assistant at Observer Research Foundation; Vaibhav Chowdhary, Associate Director of Energy Policy Centre, New Delhi; and Nikhil Pahwa, Founder of Medianama. The panelists deliberated upon solutions to develop a more robust cybersecurity regime in India. This session was moderated by Kazim Rizvi, from The Dialogue.

Nikhil concluded the session with five questions to ponder on, linked to the minimum

security requirements in India for any entity to collect data, to store data, to transfer data, how is this data being protected, and finally how can citizens ensure that this data is secure? The concerning trend in India of registering FIRs against individuals who identify vulnerabilities in systems, especially essential government systems such as electronic voting machines or UIDAI1, was highlighted. The session ended with the question of how we can ensure that people will report issues in a responsible manner, following rules and norms, given such a chilling environment of data security issues. For the end users, Nikhil recommended encouraging a sensibility of mistrust in the ecosystem as well, given cases in India and elsewhere wherein people unsuspectingly share sensitive data such as bank account details.

| SESSION | RECOMMENDATION | TARGET STAKEHOLDER |

| Going beyond privacy: The social justice implications of surveillance culture by Internet Democracy Project | While governmental measures for surveillance effectively monitor all citizens, these mechanisms often fall short of actually delivery of entitlements. A number of citizens still face hurdles in accessing rights and entitlements to health services, food, medicines, etc., and thus the systems have great scope for improvement in delivery and implementation at the ground level. | Government |

| Certain surveillance measures, with due emphasis on proportionality in their impact on rights, are helpful for public safety. However, they require efficient implementation, ensuring that the technological systems designed are able to deliver what they are intended to achieve. For instance, CCTV cameras on installed on roads in major cities intended to check traffic violations and accidents are failing to do so due to non-functionality of units and design failure in their inability to work in dark conditions. Such implementation and technology failures can be easily addressed with more efficient administration. | Government | |

| Industry 4.0 and cyber security: Confronting challenges by The Dialogue (Roundtable) | Competitors in the industry must comply with regulation because technology has economic impact and legal implications. Industry players and government must fuse and adopt a more proactive risk management approach to make an integrated policy framework. The industry needs to help the government with making cybersecurity guidelines as the government does not possess the knowhow on how technology can be used to detect threats. | Private Sector, Government |

| The government needs to provide legal solutions with a robust and precise law, with standardised frameworks of definitions regarding what constitutes cyber crimes. |

Government | |

| Law will face challenges in implementation without a robust mechanism for detection, thus the industry needs to collaborate with government to develop such infrastructure. | Private Sector | |

| Businesses needs to adopt a more holistic approach in evolving a technologically strong solution for cyber crimes in which they need to invest without expectation of any direct economic returns. | Private Sector | |

| We need to be proactive when it comes to overcoming legal loopholes: instead of waiting for interpretation and criticism by the court and regulators, it is more effective to evolve multi-stakeholder platforms for deliberating on a more robust regulatory environment. | Private Sector, Government | |

| Sensitise the government, police, and courts about cyber risks and technologies that can have an impact in the ecosystem. Adopt best business practices in a reasonable and adaptable manner by taking advantage of international precedents alreadym in place. |

Private Sector | |

| Government can initiate with the right policy environment, fiscal incentives, cheaper loans in order to build a conducive environment, which facilitates and promotes the right kinds of innovation. The biggest challenges in India are related to lack of skilled and trained manpower, and lack of investments into innovation and tech transfer. | Government | |

| Develop a fundamental set of stricter guidelines with reference to security and not merely voluntary policies. | Government, Private Sector | |

| India’s policy on data transfer over mobile phone, with 44 bit encryption, is disturbing and open to vulnerabilities. | Government | |

| Robust public disclosure and appeal mechanisms for holding government bodies and private players accountable in case of data breaches must be developed. | Government |

The summit’s final theme focused on Freedom of Expression, under which the following

sessions were organised:

- Don’t Let it Stand: How do women deal with online abuse? Curbing the freedom of expression for women in digital spaces by Internet Democracy Project and Feminism in India (Panel)

- Feminists taking over of the web using ICTs by Hidden Pockets, Point of View, and Feminism in India (Roundtable)

- Legally ‘Obscene’ – Law, Gender, and Digital Rights by Point of View (Workshop)

Don’t Let it Stand: How do women deal with online abuse? by Internet Democracy Project and Feminism in India was an interactive roundtable dialogue on women’s and marginalised person’s freedom of expression in digital spaces, online abuse targeted at women and queer and trans persons, and potential strategies to deal with gender-based online harassment. It was facilitated by Nayantara Ranganathan, from Internet Democracy Project, and Japleen Pasricha, from Feminism in India. The remaining panelists were Piyush Aggarwal, from Hindustan Times, and Prasanth Sugathan, from SFLC. The session addressed legal and nonlegal measures to combat online harassment, and evolved several strategies to deal with it. It also identified several gaps which exist in the implementation of already existing systems, namely: language gaps as mechanisms for checking abuse on online platforms cannot detect local Indian languages written in Roman script, inability to deal with automated abuse, and societal and attitudinal gaps in terms of women’s access to technology.

Legally ‘Obscene’ – Law, Gender, and Digital Rights by Point of View focused on gender issues with regard to obscenity and complexities of cybercrime. It was a workshop facilitated by Bishakha Datta, from Point of View. It was designed as a participatory workshop, wherein all participants were divided into four groups, and each group was assigned a case involving the use of the internet as a medium to perpetrate violence or harassment, for example a politician being mocked on twitter, online harassment by an intimate partner, harassment through rape video, etc. The groups were given 10-15 minutes to discuss the harms involved in the case, such as the misuse of law, communal issues, infringing the freedom of expression, etc. The session identified several areas of ambiguity within existing systems. Cybercrimes involve many complexities and fluid boundaries. For instance, there is a very fine line between online satire and defamation. Another complication is when cybercrimes are committed by individuals across borders, it becomes extremely difficult to identify and catch hold of the perpetrator. The definition of obscenity is another convoluted area. The scope of considering humor and political satire within the ambit of obscenity often infringes on citizens’ freedom of expression.

Feminists taking over of the web using ICTs by Hidden Pockets, Point of View, and Feminism in India focused on women’s access to and use of the Internet. It focused on three questions under this theme: how women access and share information; how women make use of the Internet for development; and, how does the Internet help women integrate with mainstream society? The panelists were Jasmine George and Aisha George from Hidden Pockets, Bhani Rachel Bani from KrantiKali, Payel Ganguly, and independent Python and CSS coder Japleen Pasricha from Feminism in India. The session highlighted the ways in which civil society groups can effectively harness the Internet and different multimedia strategies to mainstream gender issues, and spread awareness among communities especially the youth which are major users of the same. Two such successful initiatives discussed are Hidden Pockets’ podcasts and the ‘Own Your City’ initiative, wherein women log their experiences of living in cities in order to create their own feminist maps, Another successful initiative discussed is KrantiKali’s use of memes for gender sensitisation targeted at youth between ages 15-25.

Impact of Internet shutdown in India was organsied by Digital Empowerment Foundation (DEF) and Software Freedom Law Centre (SFLC). Prashanth Sugathan, Legal Director, SFLC moderated the session with Vaishali Verma (Counsel, SFLC.in), Ritu Srivastava (General Manager, Research and Advocacy, Digital Empowerment Foundation) and Sarath MS (Technologist, SFLC.in) speaking about various aspects of the topic.

The session started with an overview of internet shutdowns and SFLC and DEF’s efforts tracking instances of internet shutdowns in India. Vaishali Verma emphasized the need for Internet in light of the government’s push towards ‘Digital India’. The steep rise in the number of shutdowns since 2012 has been remarkable and in 2017 alone, 56 shutdowns in the country have been recorded. She discussed the experiences of affected residents and the new rules for Temporary Suspension of Telecom Services in case of public emergency and public safety, issued by the Department of Telecommunications, and its shortcomings. Lastly, she underlined the economic losses faced by the country due to the Internet shutdowns.

Ms. Ritu Srivastava dealt with the nature and psychological impact of Internet shutdowns. She cited several instances in which Internet shutdowns had profound psychological impact on people of all ages. It directly affects right to life and livelihoods and the right to access information. In many instances, the state shuts down network in name of national security, to prevent the spread of fake news and rumors, and to prohibit communal violence. She shared examples of incidents when social media has been used by administrators to control such situations. She emphasized that shutdowns are not the solution to maintain national security. She critically questioned the transparency and accountability of shutdowns by the state and telecom providers. With neither the state nor telecom providers providing any notification prior to shutdowns. She questioned community guidelines put forward by corporate platforms, their inefficacy and the community they actually seek to serve.

FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION: RECOMMENDATIONS

|

SESSION |

RECOMMENDATION |

TARGET STAKEHOLDER |

| Don’t Let it Stand: How do women deal with online abuse? Curbing the freedom of expression for women in digital spaces by Internet Democracy Project and Feminism in India (Panel) | Systems for checking online gender- based harassment, whether designed and implemented by governments, private sector, or civil society, should successfully close feedback loops, wherein concrete steps to address – and not merely register – women’s complaints are adopted. One such example is Vodafone’s initiative to register simcards without sharing personal details, after receiving complaints of women’s personal details being compromised. | Government, Private Sector, Civil Society Organisations |

| Civil society initiatives must encourage partnerships among different groups to organise workshops on simple digital security and online hygiene practices that all users, irrespective of technical expertise, can adopt. | Civil Society Organisations | |

| Legally ‘Obscene’- Law, Gender, and Digital Rights by Point of View (Workshop) | Section 67 of the IT Act, 2008 is referred to as the anti-obscenity provision. The wording of the provision is identical (with a few additional changes) to that of the anti-obscenity provision of the Indian Penal Code which was formulated in 1860. Section 67 uses complicated colonial era terms like ‘lascivious’ and ‘prurient’. The language makes it difficult for police officers to understand the application of the provision. The applicability and relevance of this Section of the IT Act needs to be reassessed in the current times, especially the language of the provision needs to be simplified for it to be easily understandable by different stakeholders and minimize any scope for ambiguity. | Government |

| The law must maintain a healthy balance between individual and community harm. Online content could be funny for some and hurtful for others. The line must be drawn in such a manner that doesn’t infringe on the freedom of expression. Usage of wide and vague terms like ‘hurting religious sentiments’ to punish people for sharing online content needs to be reexamined. | Government | |

| In order to protect different genders from sexual harassment, both online and offline, there is a need to introduce gender neutral laws. This will give every individual, irrespective of their gender, an equal footing to get justice when their bodily privacy and sexual autonomy is violated. | Government | |

| Impact of Internet shutdown in India | Define “national security” andwhat it entails in the context of internet shutdowns | Government |

| There is need of continuous advocacy not only from civil society but also from telecom sectors who are serving the large community to government to be accountable and transparent when internet shutdowns are imposed; | Civil society and telecom operators |

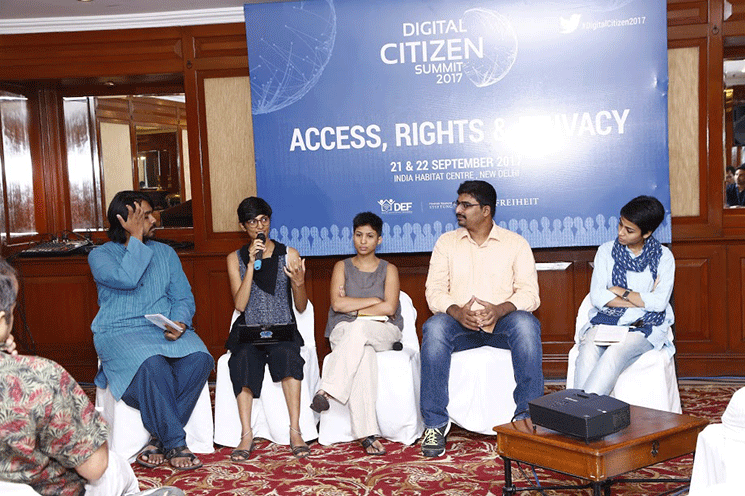

This session, the third edition of Delhi Tech Talks, included a panel which deliberated on the state of digital rights in India. It focused on the themes, trends, and priority areas across the tech law and policy space. The panelists included Osama Manzar, founder of Digital Empowerment Foundation; Sumandro Chattapadhyay, Research Director at Centre for Internet and Society; Tulika Pandey, Scientist at Department of Electronics and Information Technology, Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology, Government of India; Prasanth Sugathan from SFLC; and Chinmayi Arun, Executive Director of Centre for Communication Governance, National Law University Delhi. The presence of multiple stakeholders representing the perspectives from grassroots, government, civil society, and legal and policy expertise ensured a very lively and contentious discussion touching upon the most recent and pressing concerns in India such as the Aadhaar project and Right to Privacy judgment.

HIGHLIGHTS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

- Priorities taken up in digital rights spaces and deliberations must incorporate ground reality concerns in India today. The present discussion framed in concepts of rights, access, privacy, security, and transparency are often alien from the ground reality, wherein people are primarily concerned with timely receipt of their entitlements. Some of the other issues being discussed on legal and policy tables

such as privacy or security are not yet part of their everyday life. Such discussions must take greater account of the Indian context. Culturally and functionally we are an oral country and prefer to orally disseminate information and communicate. Most of us are generationally remain a society that lives together, and not in private. In such a context, there is little cultural understanding of privacy or the need for it. Finally, 70% of our population is rural, unconnected, and non digital. However, even the poorest of the poor which may never have seen a digital device is subject to government entitlements only if the digital plays a role. This highlights the primary importance of access and digital literacy.

Counter: We should appreciate and emphasise our diversity rather than create a uniform and homogeneous idea of an ‘Indian culture’. It is far reaching to prescribe all of these values to Indian culture in general. It looms dangerously close to ascribing our values onto other cultures and societies within India. - The government is attempting to integrate technology such as Aadhaar into broad-reaching support systems for the citizens, which are designed to deliver entitlements and services to the poorest of the poor citizens. In policy making, the government also needs to account for multiple factors and weigh in each rather than giving primacy to one, such as cultures, economies, access, as well as citizen responses. And while the government is aware of the security aspect of such projects, the intention is not to take away data but to reach benefits to the public and cater to the large population and varied requirements of the country through integration of technology.

Counter:Technology should enable choice, and the Aadhaar project robs us of our choice because it is being made a compulsion to access all entitlements. Coercion is one of the major problems with the project. The other major flow of the project is regarding full disclosure and informed choice, and its failure to inform the public of potential risks that giving away personal information carries. The government’s concern with citizen welfare should extend to the point of allowing the exercise of choice. - Despite the orality and sensibilities surrounding privacy in many Indian cultures, it is clear that people in India care for privacy. This is manifested in the negotiations that take place whenever citizens are required to provide any kind of data to the government. The kind of data being given by people to governments depends on who is asking, what is being asked, what are the terms and conditions. Thus, our relationships with data and privacy is always a negotiation depending upon context and other factors, and not a uniformly uncaring attitude towards privacy.

- It is concerning that we are raising the data protection question after data-collection systems have already been institutionalised. Instead, data protection should have been a top level primary concern, to be addressed in the initial design of the system. In the future, we must build systems that actually protect data along with having robust legal mechanisms for data protection, accountability, and redress. Presently, we must deliberate over the long term implications of data breaches that have already occurred in such systems.

- Another concerning trend in India is that of Internet shutdowns, which have been on the rise on a yearly basis. SFLC has tracked 57 shutdowns in this year alone. This is a disturbing trend and not the way to digitalise, as it impinges on citizens’ right to access the Internet and people’s access to information and knowledge.

Digital Citizen Summit 2017 concluded with a Special Session: Enactment of Right to Privacy courtroom proceedings.

This session demystified the right to privacy judgement, highlighting the key sets of arguments and counter-arguments. An expert panel consisting of lawyers Usha Ramanathan, Apar Gupta, Amba Kak, and Kazim Rizvi simplified and explained the key arguments of the 547-page judgment for the audience. Key arguments were picked up from the judgement and each panelist gave their take on it and the implications on future fights with respect to the Aadhaar bill, data protection, Section 377 among others.

The concluding ceremony of the summit discussed the outcomes and recommendations

gleaned from the thematic sessions spread over the previous two days. It was led by Reuben Dieckhoff, Regional Project Manager for South Asia, Friedrich Naumann Stiftung für die Freiheit and Osama Manzar, Digital Empowerment Foundation.

The way forward for the summit was discussed, with the hope to evolve DCS as a parallel IGF in the future. It was reiterated that DCS should be developed as a platform for South Asian participation for deliberation on pressing issues surrounding the digital.

Recommendations will be collected from all participants to make the summit a more inclusive and democratic space.

Emerging issue papers and briefing papers have come from the summit, which can be further used for advocacy. The key highlights and recommendations gleaned from the summit deliberations are presented in the following section.

HIGHLIGHTS AND OVERALL RECOMMENDATIONS

- Defining the Digital

Internet architecture rests on collaboration and sharing, and this nature should be preserved and promoted in national drives to go digital. Such drives must emphasise ambitions towards citizenship rather than appropriation. However, while the digital offers many exciting and new opportunities for the exercise of rights, citizenship should not be reduced to the digital. The digital must be promoted with view to preventing real-world exclusions of the poor and marginalised from being reproduced online. The promotion of the digital should espouse the ideals of citizenship, which is rights-based and inclusive. - Defining Citizenship

The goal of citizenship should be ensuring State accountability. Thus, the exercise of citizenship should not be passive but an active one, and must be aimed at promoting and protecting everyone’s rights. In India, the structure of the State already provides many avenues for demanding accountability. Therefore, citizens must demand for and access systems of accountability, appeal, and redress. - Adopting Rights-based and public interest approaches

The goal of the summit was to encourage the adoption of right-based approaches in drives to go digital. The session on Connecting India’s Billion by The Dialogue presented a particularly succinct case for such an approach. From the public interest and rights perspective, connectivity is not only about the numbers but people’s experiences over the Internet. An open internet has much more value to society rather than a controlled telecom service. However, the principle of openness must not remain in the abstract conversations at the international level for ideal policy, they must be applied to concrete measures adopted on the country level. While the stakeholders in these international

debates are countries and telecom providers, the ultimate stakeholders are the public, which often pays tax money for governments to deliberate on policy and infrastructure as citizens and also pays the telecom industry as consumers. Although the general public very rarely gets the opportunity to participate in policy discussion, mechanisms must be developed to ensure its perspective is given due consideration in policy dialogue. - Emphasising multi-stakeholderism

In order to evolve more effective laws and policies, there is a need to engage with and create more multi-stakeholder platforms, such as DCS. The aim of such platforms is to build consensus by bringing to light the various kinds of differences of opinion and experience that exist between several stakeholders in the Internet ecosystem. They also demonstrate in practice that we must engage with different institutions in different ways, depending on their nature of operation, and ensure that appropriate authorities hear out perspectives of other stakeholders and are then able to incorporate them into laws and policy. Such platforms must encourage greater collaboration and partnerships in order to facilitate knowledge exchange whether between governments, between government and private players, business to business, or with civil society organisations. Civil society needs to take a lead in facilitating, creating, and demonstrating such knowledge platforms with government support. Government also needs to build a conducive environment and invest some initial seed money in research and development, and training and capacity building. - Nature of solutions

Several sessions cautioned against adopting one stop or ‘one size fits all’ solutions to digital problems. The session Don’t Let it Stand by Internet Democracy Project

and Feminism in India in particular aptly framed the recommendation. Since digital problems are of different nature, one stop solutions, either tech-based or law-based, are not enough to combat the given challenges. Instead, relying only on one form of response may be exclusionary in practice. Therefore, effective strategies must be blended and multi-pronged, and involve strategic and context-appropriate partnerships between governments, private sector, civil society, and communities. Solutions to many problems relating to the exercise of human rights online may be legal or nonlegal. Non legal solutions may be individual, community-based, or led by civil society organisations or private sector organisations, and partnerships among them. The solutions adopted must be context-appropriate, multi-pronged, and involve different kinds of partnerships rather than one stop shop solutions to each problem. For instance, social and attitudinal problems preventing women and girls from accessing technology could be community-based, while solutions to regulate search engines could be both legal and market-based. - Governance systems

We must aspire to build systems of governance that are democratic, i.e., which enable citizens’ right to information and emphasise State disclosure; rather than autocratic which focuses on information surveillance and data gathering at the cost of citizens’ rights. The governance systems we design should emphasise proportionality, and involve only minimal violation of rights. - Overcoming challenges to going digital

Governments across the world have initiated huge drives to go digital and integrate technology. However, significant challenges remain, especially in developing countries. These challenges may be infrastructural, political, or societal. In terms of infrastructure, digital drives would be inadequate without improving and making accessible other basic infrastructure, such as reliable electricity. Access remains a key concern not only in terms of service delivery but as a right. To not have access in a connected world is a serious violation of human rights. Challenges to access must be mapped more efficiently. It is necessary to profile the unconnected, as they are also marginalised in other ways: they are poorest of the poor, geographically farreached, indigenous people, and a good number live in India and Asia. For ensuring last mile connectivity, access can be provided not only directly to individuals, but through institutions. However, such drives must also avoid the false tradeoff created between privacy and access in such debates. We need to emphasise that there are certain things that we, as citizens, consumers, or end users, cannot give up. In political terms, digital drives are meaningless in countries inclining towards greater censorship and network shutdowns. In societal and attitudinal terms, the case of India and other countries shows that marginalised social groups such as women face many barriers to accessing online platforms. We must ensure that everyone has equal opportunities in the digital.

George Abraham, Score Foundation

George Abraham, CEO of Score Foundation, started his career in advertising in 1981 and started working with the blind after 1989. Having spent over two decades working in the domain of Life with blindness, George has diverse experience as a trainer/motivational speaker, a promoter of cricket for the blind and a disability Activist/Communicator.

Ashish Aggarwal, National Institute of Public Finance & Policy

Ashish Aggarwal is a financial sector and policy professional consulting for National Institute of Public Finance & Policy, New Delhi.

Piyush Aggarwal, Hindustan Times

Piyush is a data researcher with Hindustan Times. He primarily works with data to tell stories and experiments with algorithms for automated journalism. Piyush also works on social network analysis using natural language processing and machine learning.

Sayeed Ahmad, Center for Social Activism

Sayeed Ahmad works at Center for Social Activism, Bangladesh.

Chinmayi Arun, Centre for Communication Governance, NLU

Chinmayi Arun is an Assistant Professor of Law at National Law University Delhi, and the Executive Director of the Centre for Communication Governance. She is a member of the Indian Government’s multi stakeholder advisory group for the India Internet Governance Forum, a member of UNESCO India’s Press Freedom committee, and has been a consultant to the Law Commission of India in the past. She is also a Faculty Associate of the Berkman Klein Centre at Harvard University.

Renu Arya, Feminist Approach to Technology

Renu Arya works at Feminist Approach to Technology, a not‐for‐profit organization that believes in empowering women by enabling them to access, use and create technology through a feminist rights‐based framework.

Htaike Htaike Aung, Myanmar ICT for Development Organisation

Htaike Htaike Aung is a digital security & privacy trainer/consultant for human rights defenders in Myanmar and is co-founder and Executive Director of Myanmar ICT for Development Organization (MIDO). MIDO is one of the very few ICT-focused non governmental organization in Myanmar/Burma.

Bhaani Rachel Bali, KrantiKālī

Bhaani Rachel Bali is the founder of KrantiKali, a social startup based in Delhi and Mumbai advocating feminism and gender equity through creative means across India.

Anoo Bhuyan, The Wire

Anoo Bhuyan is a journalist covering health policy for The Wire. She has previously worked with Outlook Magazine, National Public Radio, and BBC.

Arpita Biswas, Centre for Communication Governance, NLU

Arpita Biswas is an Analyst with the Centre for Communication Governance, NLU.

Sumandro Chattapadhyay, Centre for Internet and Society

Sumandro Chattapadhyay leads academic, creative, and policy research at the CIS as its Research Director. The core policy topics that Sumandro engages with include open data and open research, e-governance and digital ID, and network economy and digital labour.

Raman Jit Singh Chima, Access Now

Raman Jit Singh Chima is Policy Director at Access Now, leading the global policy staff working on protecting an open internet and advancing the rights of users at risk across the world. He is a graduate of National Law School of India University, Bangalore, and has previously served as Policy Counsel and Government Affairs Manager with Google based in Delhi, and advised government, industry bodies and academia on technology policy issues.

Vaibhav Chowdhury, EPIC-India

Vaibhav Chowdhary is Associate Director, Operations and Strategy, at EPIC-India (Energy Policy Institute of the University of Chicago), New Delhi. He is an Electronics and Instrumentation Engineer with an MBA in Power Management from National Power Training Institute (NPTI), GoI.

Bishakha Datta, Point of View

Bishakha co-founder of Mumbai-based non-profit Point of View, and is a nonfiction writer and documentary filmmaker with an abiding interest in representing invisible points of view and people – people who are marginalized because of their genders or sexualities, or voices that are unheard, ‘illegitimate’ or silenced.

Saikat Datta, Centre for Internet and Society

Saikat Datta is former Editor (National Security) of Hindustan Times, Delhi. He has beena journalist for over 19 years, writing on the intersection of government, policy, security, intelligence, and defence. His work has been awarded the International Press Institute award, the National RTI award for investigative journalism and the Jagan Phadnis Memorial award for investigative journalism.

Ruben Dieckhoff, FNF

Ruben Dieckhoff, graduated from Heidelberg University where he studied political science with a focus on international relations and economics. Prior to joining FNF in 2012 as Project Manager South Asia, he worked as management consultant in Berlin. He has a keen interest in everything related to digitization, human rights, and economic developments.

Gauthamraj Elango, F-Infotech

Gauthamraj Elango works on digital literacy and access, and runs a cyber cafe in

Perundurai, a tier 3 town in Tamil Nadu.

Payel Ganguly

Payel Ganguly is an independent Python and CSS coder.

Liza Garcia, Foundation for Media Alternatives

Liza Garcia specialises in women’s rights and ICTs, and is the Executive Director of Foundation for Media Alternatives, Philippines.

Aisha Lovely George, Hidden Pockets

Aisha Lovely George heads the operations, Mapping and Podcasts at Hidden Pockets. She is certified as a peer educator by Enfold India and has conducted several training on Sexual and Reproductive health for Government school students and also for students from community library; and is one of the Youth Champions 2017 from India (of the Asia Safe Abortion Partnership).

Jasmine Lovely George, Hidden Pockets

Jasmine is the founder of Hidden Pockets, and believes in the idea of creating radical spaces for discussions and narratives. A lawyer and activist, she intends to create critical discussions while practising her dance moves until revolution knocks her door some day. For her, Hidden Pockets is a step towards merging city and development with a pinch of sexuality in it.

Asmita Ghosh, Feminism in India

Asmita Ghosh is Digital Editor at Feminism in India.

Parveer Singh Ghuman, CUTS International

Parveer Singh Ghuman is senior research associate at CUTS International, and has a background in law.

Anil Kumar Gupta, MicroSave

Anil Gupta is Associate Director, DFS-MNO & ANM Domain, MicroSave. He is a development banker and technology manager with over 18 years of experience in projects with development banks, commercial banks, international funding agencies, MFIs, community-based institutions, rural infrastructure projects, and major Telecom players in India, China and USA.

Apar Gupta, Advocate

Apar Gupta studied at Amity Law School where he merged his two interests – technology and the law. Gupta wrote Commentary on Information Technology Act, published by Wadhwa and Company. After completing his education, he joined Karanjawala and Co. to start his career as a litigator. He regularly advises the Internet and Mobile Association of India on new regulations in the sector. Vigneswara Ilavarasan, IIT Delhi Dr. Vigneswara Ilavarasan is an associate professor in the Department of Management Sciences at IIT-Delhi. His teaching interests include social media and business practices, ICTs in relation to development and business, Management Information Systems (MIS), eCommerce, market and business research methods.

Dhrubo Jyoti, Journalist

Dhrubo Jyoti is a queer Dalit activist and journalist by profession working with Hindustan Times, New Delhi.

Brindaalakshmi K, Hidden Pockets

Brindaalakshmi. K writes poetry, journalistic pieces, screenplay, brand copy, social media copy, fiction and anything else with a promise of an exciting challenge. Having spent too much time studying startups as a business & technology journalist, she now prefers spending her time branding and building businesses instead.

Amba Kak, Mozilla Technology Policy Fellow

Amba Kak is a Mozilla Technology Policy Fellow, and a graduate of Oxford Internet Institute and National University of Juridical Science (NUJS). She has previously worked as legal consultant with National Institute of Public Finance & Policy, coordinator for National Campaign for People’s Right to Information, and Google Policy Fellow with CIS Bangalore.

Vikas Kanungo, Sr. Consultant World Bank, eGov & mGov

Vikas Kanungo is an e-Government and m-Government expert with more than 20 years of experience in the field of ICT, e-Governance, m-Governance, Open Data/Big Data, Social Media technologies and cloud computing.

Padmaja Karra, Amnesty International India

Padmaja Karra is Human Rights Campaigner at Amnesty International India.

Gayatri Khandhadai, Association for Progressive Communications (APC)

Gayatri Khandhadai is the Project Coordinator for APC IMPACT (India, Malaysia, Pakistan Advocacy for Change through Technology) project. She is a lawyer with a background in international law and human rights, international and regional human rights mechanisms, research, and advocacy.

Srinivas Kodali, Open Stats

Srinivas Kodali is a civil engineer, researcher, and entrepreneur working on urban transportation and digital technologies in India. He is a user, contributor to open data, civic tech and cyber security. He is currently working on Open Stats, an open data company based out of Hyderabad.

Padma Koppa, Amnesty International India

Padma Koppa is Manager of Mobilisation at Amnesty International India.

Anja Kovacs, Internet Democracy Project

Dr. Anja Kovacs directs the Internet Democracy Project in Delhi, India, which works= for an Internet that supports free speech, democracy and social justice in India and beyond. Anja’s research and advocacy focuses especially on questions regarding freedom of expression, cybersecurity and the architecture of Internet governance.

Amol Kulkarni, CUTS International

Amol Kulkarni works with CUTS International, an international non-profit nongovernment economic policy research outreach organisation, at its Centre for Competition, Investment, and Economic Regulation in Jaipur, India. He leads research projects on regulatory, competition, and consumer protection reforms, primarily in financial sector.

Aklima Ferdows Lisa, Center for Social Activism

Aklima Ferdows Lisa is an activist working with Centre for Social Activism, Bangladesh.

Nipun Malhotra, Nipman Foundation

Nipun Malhotra is founder and CEO of Nipman Foundation, working in the areas of health, dignity, and happiness for persons with disabilities and underprivileged groups.

Rupsa Mallik, CREA

Rupsa Mallik is Director, Programmes and Innovation, at CREA

Sunil Mathew, Society for Rehabilitation of Visually Challenged

Sunil Mathew is Secretary at Society for Rehabilitation of Visually Challenged, which works on providing opportunities of employment to the visually challenged by taking advantage of technology especially in telemarketing and computer training.

Sarath MS, Software Freedom Law Centre

Sarath MS is a FOSS activist and software engineer working at SFLC.in. He has a bachelor’s degree in Computer Science and has nine years of professional experience in software development.

Nadika Nadja

Nadika is a transwoman and writer currently based in Bangalore.

Nicolas Andres Pace, AlterMundi

Nicolas Andres Pace is core developer of LibreRouter project at AlterMundi, a NGO

based in Argentina. LibreRouter is an Open Software Open Hardware Router for and by Community Networks.

Nikhil Pahwa, Media Nama

Nikhil Pahwa is an Indian entrepreneur, journalist, publisher, and founder and owner of MediaNama, an India-based mobile and digital news portal. He has been a key commentator on stories and debates around Indian digital media companies, censorship and Internet and mobile regulation in India.

Tulika Pandey, Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology

Tulika Pandey is Scientist at Department of Electronics and Information Technology, Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology, Government of India.

Jayadev Parida, Observer Research Foundation

Jayadev Parida is a PhD scholar pursuing cybersecurity at Jawaharlal Nehru University and Research Assistant at Observer Research Foundation.

Smriti Parsheera, National Institute of Public Finance & Policy

Smriti Parsheera is a lawyer and public policy professional consulting for National Institute of Public Finance and Policy, New Delhi.

Japleen Pasricha, Feminism in India

Japleen smashes the patriarchy for a living. She is a sex positive, intersectional feminist,nwriter, educator, and researcher. Her interests include gender, media, and technology. She tweets @japna_p.

Pranto Polash

Pranto Polash is a Bangladeshi journalist now residing in India who has been a

victim of Section 57 of the Bangladesh ICT Act.

Smitha Krishna Prasad, Centre for Communication Governance, NLU

Smitha Krishna Prasad is a senior member of the Technology, Media and Telecoms,

Intellectual Property and International Commercial Laws practice group at CCG, and focuses on matters pertaining to data privacy, information technology, intellectual property, telecommunications, media and entertainment laws.

Usha Ramanathan, Legal Researcher

Dr. Usha Ramanathan is an Advocate and legal researcher with expertise on law and

poverty.

Ranjeet Rane, The Dialogue

Ranjeet is an award-winning author and regularly publishes his ideas in leading

Indian publications. Ranjeet has a master’s degree in Political Science along with certifications in Public Policy, Cyber Laws, and Ethical Hacking. He blogs and tweets as the Old Wonk. At The Dialogue, he leads on all things Internet Governance.

Nayantara Ranganathan, Internet Democracy Project

Nayantara manages the Freedom of Expression programme at the Internet Democracy Project where she works on the planning, co-ordination, research and advocacy of projects related to freedom of expression issues in India, as they relate to gender and the Internet, net neutrality and surveillance. She studied law at the National University of Juridical Sciences, Kolkata.

Kazim Rizvi, The Dialogue

Kazim is a public policy professional based out of New Delhi. He is passionate about bringing a positive discourse in India’s political and policy space, and envisages to make a lasting impact. The Dialogue was founded with this idea in mind.

Anupam Sanghi